written by Lauren Fields, Founder of Yoga to You and Mobile Yoga Academy

The other day, as a potential student was coming to chat about her interest, I noticed a pang of insecurity: "My studio is so humble, and I am the only teacher."

〰️

The other day, as a potential student was coming to chat about her interest, I noticed a pang of insecurity: "My studio is so humble, and I am the only teacher." 〰️

How to Choose a Yoga Teacher Training: Three Essential Questions to Ask Before You Enroll

When you search for 200-hour yoga teacher trainings, thousands of options appear: local programs scheduled quarterly, intensive 30- or 40-day immersions, destination trainings in gorgeous locations with food and lodging included. Before diving into this sea of choices, it helps to understand where yoga teacher training came from—and where it's going.

A Brief History of Yoga and Its Journey to the West

Yoga originated in ancient India over 5,000 years ago, with early references appearing in the Vedas and Upanishads. For millennia, yoga was transmitted through the guru-shishya (teacher-student) tradition—one teacher working with one or two students over many years, often with the student living in the teacher's home. This intimate model shaped how yoga knowledge was preserved and passed down through generations.

The practice remained largely unknown in the West until the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when several key figures began bringing Eastern wisdom across the ocean.

Timeline: Yoga Comes to the West

1893

Swami Vivekananda addresses the Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago, introducing Vedanta and yoga philosophy to America. His 1896 book Raja Yoga marks the beginning of modern yoga's influence in the West.

1920s–1930s

Paramahansa Yogananda arrives in Boston (1920), later founding the Self-Realization Fellowship in Los Angeles. Meanwhile in India, T. Krishnamacharya opens the first Hatha yoga school in Mysore (1924) and begins training the students who will reshape global yoga.

1950s–1960s

Walt and Magana Baptiste open a yoga studio in San Francisco (mid-1950s). Swami Vishnu-devananda arrives in San Francisco (1958) and publishes The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga (1960). The counterculture movement sparks widespread interest in Eastern practices.

1965–1970s

U.S. immigration law changes (1965) allow more Indian teachers to settle in America. B.K.S. Iyengar appears on BBC (1963) and becomes internationally known. Swami Satchidananda opens Woodstock (1969). Pattabhi Jois makes his first U.S. visit (1975), igniting the Ashtanga movement.

1970s–1990s

Bikram Choudhury opens his first U.S. studio in Beverly Hills (1973) and popularizes hot yoga. The first issue of Yoga Journal is published (1975). Bikram begins nine-week teacher certification courses in the 1990s, training thousands of instructors.

1999

Yoga Alliance is founded, establishing the 200-hour and 500-hour certification standards that remain the industry benchmark today. This standardization makes yoga teaching a viable career path and opens the floodgates for teacher training programs.

2000s–Present

Teacher trainings proliferate globally, becoming a significant revenue stream for studios. The multi-teacher "faculty" model emerges as studios hire specialists for different modules (anatomy, philosophy, sequencing). Vinyasa flow becomes the dominant Western style. By 2023, Yoga Alliance reports over 90,400 registered teachers and 6,200 registered schools worldwide.

The Major Lineages: Who Taught Your Teachers?

Nearly every style of yoga practiced in the West today traces back to one remarkable teacher: T. Krishnamacharya (1888–1989), often called the "Father of Modern Yoga." His four most influential students each developed distinct approaches that shaped the yoga landscape:

B.K.S. Iyengar (1918–2014)

Iyengar Yoga: Emphasizes precise alignment and the use of props (blocks, straps, bolsters). Known for long holds and therapeutic applications. His book Light on Yoga (1966) remains a foundational text.

K. Pattabhi Jois (1915–2009)

Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga: Dynamic, physically demanding sequences synchronized with breath. Divided into six series of increasing difficulty. The foundation for modern "power yoga" and vinyasa flow.

T.K.V. Desikachar(1938–2016)

Viniyoga: Krishnamacharya's son, who developed a highly individualized approach. "Teach what is appropriate for the individual" became the guiding principle. Considered a pioneer of yoga therapy.

Indra Devi (1899–2002)

Known as the "First Lady of Yoga," she was among the first women and the first Westerner to study with Krishnamacharya. She taught yoga to Hollywood celebrities and helped popularize the practice in the Americas.

Other influential lineages include Bikram Yoga (26 postures in a heated room, developed by Bikram Choudhury in the early 1970s based on teachings from B.C. Ghosh), Sivananda Yoga(founded by Swami Sivananda, who wrote over 200 books on yoga), and Kundalini Yoga(brought to the West by Yogi Bhajan in 1968).

Understanding lineage matters because it explains why teachers teach the way they do. When you know who "bit" your teacher—metaphorically speaking—you can trace the bloodline of your own practice back to its source.

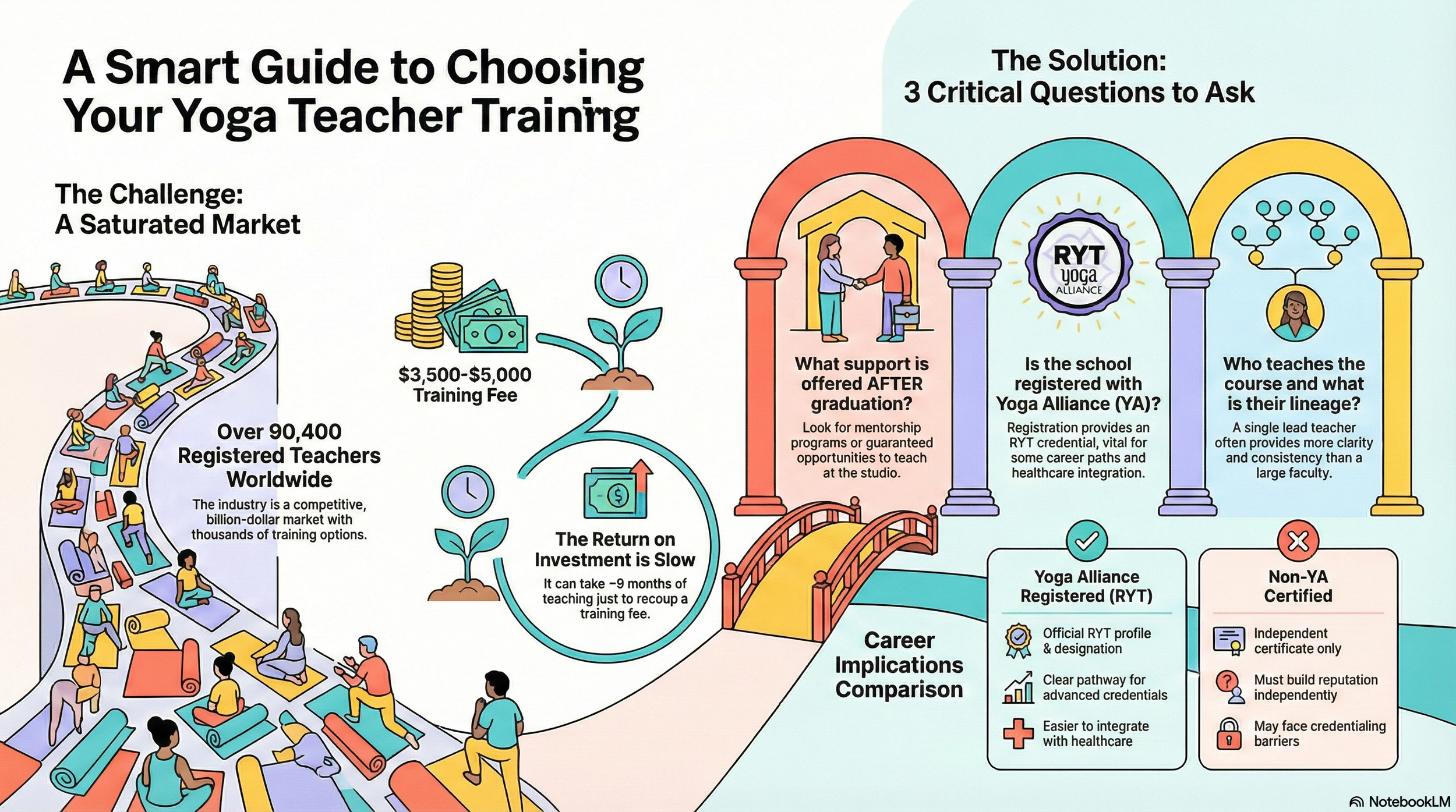

Three Questions to Ask Before Choosing a Training

Once you've narrowed down your non-negotiables—typically cost, location, and schedule (immersive versus extended)—it's time to dig deeper. The following three questions will help you evaluate whether a program will truly serve your growth as a teacher, or simply take your money and send you off with best wishes.

Question 1: What Support Is in Place After Graduation?

After the life-altering experience of your first 200-hour training—after you celebrate, share goals with your cohort, and ride the high of completing something meaningful—life resumes. The studio returns to its regular schedule of weekly classes, events, and retreats. The strong bonds you formed begin to loosen as everyone returns to their own lives.

This is when hindsight sets in. Post-graduation can feel isolating. You might find yourself thinking: "Am I ready to start teaching? Where should I apply? What do I put on my resume?"

Be specific before paying your fees. Ask to see what's written into the training contract under "deliverables." Look for concrete commitments like: "Our studio offers ongoing mentorship and an opportunity to teach or substitute with a goal of eight classes per month." If there are no substitute offerings, ask what's provided instead.

Why this matters: A studio that invests in your success after graduation demonstrates that they view your training as the beginning of a relationship, not a transaction. If the studio you love doesn't offer this support, shop around. If competitors offer mentorship and teaching opportunities, it's perfectly reasonable to advocate for yourself and ask for what you need. Since 200-hour trainings are a competitive market, studio owners may add these elements to their program to attract more students.

The economics are sobering: Yoga in the West is a billion-dollar industry. In Portland, Oregon alone, approximately 800 newly registered yoga instructors are certified annually. Trainings typically cost between $3,500 and $5,000. After graduating, the best shot at return on investment is applying to the studio where you trained, where pay ranges from $35 to $50 per class. Factor in opening, teaching, closing, and commuting, and each class represents roughly two hours of your time. At the higher rate of $50 per class, teaching twice weekly, it takes about nine months (70 classes) just to recoup your training investment—before taxes. Make sure you're getting value beyond the certificate.

Question 2: Is the School Registered with Yoga Alliance, and Does It Matter?

This has become a heated topic in the yoga community. Yoga Alliance (YA) is the internationally recognized governing body for yoga, but it's not government-licensed. Some instructors resent the annual dues and the extensive application process required to become a Registered Yoga School.

Know the difference: If you graduate from a non-YA program, you receive a certificate showing proof of training—you're a certified yoga instructor. If you graduate from a YA-registered school, you can upload your certificate to Yoga Alliance, and after verification, you become a registered yoga teacher (RYT). You receive a professional profile, logo designation, and a pathway to advance (E-RYT, YACEP, and potentially becoming a Registered School of Yoga yourself if you ever decide to become an LLC, which is a good idea in general if teaching private clients and taking events outside of a studio.

Yoga Alliance Registered

Non-YA Certified

Certificate uploaded to YA database

Certificate used independently

Professional profile and RYT designation

No formal designation system

Career pathway to E-RYT, YACEP, RYS

Can teach, lead workshops, open a studio

Can provide CEUs to healthcare industries

Limited pathways into therapeutic yoga

Easier integration with Western healthcare

May face additional credentialing requirements

From a studio owner's perspective: Becoming YA-registered is a long, tedious, and expensive process. I understand why many studios don't—or can't—do it. It can take months or years to write the handbook and wait for approval. The reason I chose to become Yoga Alliance certified is simply to give my graduates the choice. Studios that don't offer this are limiting options, especially for graduates interested in therapeutic forms of yoga or working in healthcare settings.

Question 3: Will There Be One Teacher or Multiple Instructors, and What Is Their Lineage?

This question touches on the fundamental difference between traditional and modern yoga education.

The Traditional Model: Historically, yoga was taught one-to-one. One teacher, one student—sometimes two—over years of study. The student often lived with the instructor, helping with daily tasks in exchange for lessons until the teacher deemed them ready. Schools built around a single style, like Iyengar Studios or Ashtanga Shalas, still maintain this focused approach, with one lead teacher and perhaps support staff.

The Modern "Faculty" Model: Beginning in the 1990s and accelerating after Yoga Alliance's founding in 1999, trainings increasingly adopted a multi-instructor approach. Studios began hiring specialists—one teacher for anatomy, another for philosophy, another for sequencing—believing that expertise in different areas would create a more comprehensive education. Today, large trainings may have 40 or 50 students working with multiple instructors, each teaching their section.

The results are mixed. Without naming names, feedback I've received from instructors who trained in faculty models often describes experiences as "disjointed, chaotic, confusing, disconnected." When I taught anatomy modules for another school's trainees, students would tell me that different instructors gave conflicting alignment instructions, different breathing cues, contradictory information. The only advice I could offer was to research and find out which was true—but what does that say about a trainee's confidence? Who do you believe? How do you teach when there are too many conflicting ideas?

Imagine Pattabhi Jois and Iyengar each teaching a section of the same training—it would never be done. They would argue, and there would be endless confusion among students. While it's valuable to study with multiple teachers throughout your life, having multiple teachers within a single foundational training can create chaos.

Ask these questions:

• Will there be one lead instructor or a cohort of teachers?

• What is the primary lineage of instruction?

• Who taught your teachers, and who taught them?

• If multiple instructors, how do they ensure consistency in the material?

If someone trained in Forrest Yoga and Kundalini but doesn't disclose this, students will be confused about what is what. Knowing who "bit" each of your teachers helps you understand why they teach the way they do—and how to incorporate their approach into your own practice and future teaching.

A Personal Note on Lineage and Confidence

For my upcoming training in March 2026, I'm keeping enrollment under six students and offering it in my personal home studio—a cozy space with carpet, monstera plants, crystals in the windows, light blue walls, and high ceilings. The other day, as a potential student was coming to chat about her interest, I noticed a pang of insecurity: "My studio is so humble, and I am the only teacher."

I held that thought for about five minutes before catching myself. Yoga was traditionally taught with one student and one teacher, in the humblest of places. The student would live with the instructor for years until the teacher felt they were ready.

I thought about my first teacher training, before Instagram existed, before social media beyond MySpace or chat rooms—before yoga pants were even a thing. I met my teacher Victor, 67 years old, wearing Levi's and a tucked-in T-shirt with perfect posture. He was a certified Iyengar instructor, one of the old guard who studied directly with B.K.S. Iyengar in his prime. His instruction was pure traditional Iyengar: rigidity, long holds, stoic presence while teaching form, and immense kindness emanating through firm, confident teaching.

I couldn't teach much after that training—but I could speak Sanskrit and hit the form of a pose with confidence. I was later complimented on my practice; it stood out from other instructors and was even used as a handbook reference for asana in a subsequent training. Victor gave me this because he taught me one way, and it was Iyengar. He was the vampire that bit me, and I felt bonded by bloodline to this teaching. Since then, I've completed around 800 more hours in various trainings and have learned to integrate this foundation with other modalities.

You see this quiet confidence in students of Pattabhi Jois and Iyengar alike. Both forms of yoga are potent with clarity and path: "This is how we do yoga. You are my student." I realized I was feeling insecure for keeping a training closer to how it was meant to be.

Final Thoughts

The evolution of yoga teacher training—from intimate guru-student relationships to standardized 200-hour certifications with multiple faculty members—reflects broader changes in how we package and deliver education. Some of those changes expand access and bring diverse expertise. Others dilute the clarity that comes from a singular, coherent vision.

There's no going back to the ancient model, nor should we try. But as you evaluate your options, consider what kind of teacher you want to become. Do you want a clear lineage, a direct transmission of knowledge from teacher to student? Or do you prefer a broader survey of approaches? Neither is wrong—but knowing what you're signing up for helps ensure the training will serve your goals.

Ask the hard questions. Advocate for yourself. Get the support you need in writing. And remember: whether you train with one teacher or twenty, in a humble home studio or a grand facility, the goal remains the same—to deepen your practice, find your voice, and eventually pass this knowledge on to others.

That's the lineage continuing through you.